If you will journey back to when I started this blog, I’ll remind you I was motivated by comments about the racial/ethnic make up of Renaissance Italy on a message board about the newest R&J, you can reread that post here. That message board had me pretty fired up, and I was anxiously awaiting the release of this film so that I could revisit the the topic. Well let me just get it out the way free and easy, Verona was in fact pretty darn white. Beautiful actors, some giving great performances, but yeah, it was a general wash of white. That’s a problem and disappointment for me but here’s the ticker though, that is NOT my major gripe with the film.

So I have this mission with Shakespeare – artistic, pedagogical, and the like – to remove barriers to access. I am in love with the language, with the ginormous complexity of the plays, with their messiness and where they rest on dramaturgical faultlines, but I understand that for them to exist, excite, incite, they must be accessible. This can mean many things and manifests itself in a variety of approaches. Radical adaptation can take many forms from ballet to the animated feature film, Gnomeo and Juliet. But where do we draw the line at what IS Shakespeare versus what is BASED ON or INSPIRED BY the play of Shakespeare?

I think we’ve come to respect and expect that in many cases the plays must be cut/edited. We’ve accepted the elimination or conflation of roles. Many of us are excited to see how it’s going to be done and look forward to experiencing the “director’s take.” And even those of you that begrudge modern dress/interpretations/concepts of the texts easily forgive the use of stage lighting, multi-gendered casting, or some representational stage design. That’s to say there is no one way to do Shakepeare, and any rules are only proved by the exceptions. So I’ll admit there is a sliding scale of sorts when it comes to presenting these plays. For me, there is also a tipping point.

Lord Julian Fellowes, with his screenplay for the latest feature film release of Romeo and Juliet, tips the scale too far. This production is no exception but a direct violation of the code. He has rewritten the play in such away that newcomers may think they’re getting Shakespeare when they are not. It is a radical adaptation that is calling itself the original. It’s no Gnomeo and Juliet, Rome & Jewel or Private Romeo. It presents itself as the second coming of Zeffirelli, whose Romeo and Juliet was for the better part of the 20th century the gold standard of Shakespeare film adaptation. Directed by Carlo Carlei, dressed in Renaissance garb, and even filmed in Verona, Italy, this film sets out to pull off a grand bait and switch. And what’s worse is Fellowes’ elitist attitude that anyone with less than his Cambridge education won’t understand the play without his privileged translation. How insulting. This insults the Bard, you, and me, with my public school education and degree from a mere state college. R&J is my favorite play (so much so that as soon as I type the capital letter R and the ampersand, my device auto completes R&J for me), and I understand it just fine. Most 7th graders can read the play and walk away with the basic plot line. Fellowes’ translation, let’s call it what it is, is gratuitous AT BEST. Here’s the thing, theatre and film are ALREADY a translation of text. They convert the written word into something visual, aural, vibratory, possibly tactile. Film especially has the capacity for tremendous visual translation, and literalization of metaphor. Film as a story telling medium is full of “infinite variety,” and a thoughtful director and cinematographer should be able to outwit a pompous misguided screenwriter.

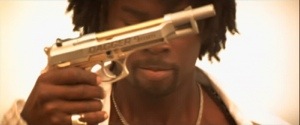

Let’s journey back to Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. A film I hardly adore, with some choppy acting by its leads, but genius in its effectiveness of rendering the story completely accessible. While Luhrmann certainly delivers an abridgment, the language he retains is Shakespeare’s, and he frames it in such a way that the audience needs no idiomatic translation of the language. Luhrmann makes the text accessible by giving his audience multiple points of entry; by recontextualizing; by suiting “the action to the word, the word to the action.” Like this brilliant example of how he handles the descriptive sword violence in the play:

Or

This visual storytelling and Luhrmann’s opening sequence, give us all the clues we need to know that Tybalt is a badass, a duelist with an “immortal passado” and a fierce “punto reverso.” Luhrmann’s translation far more effectively renders a bloody handed “civil brawl” than Fellowes’ Cambridge inspired jousting tourney which tidies up the family feud into poor sportsmanship. Fellowes does the text and the viewer a HUGE disservice. He does not deliver “the most dangerous love story ever told,” because it is the stuff of legend, but because he has practiced a most dangerous dramaturgy.

Julian Fellowes and director Carlo Carlei have mislabeled their product, have attempted to deceive, and have perpetuated the ugly myth that Shakespeare only belongs to a privileged elite. All Shakespeareans should know the damage this does to our cause. Fellowes must be an Oxfordian because we know Bill didn’t go to Cambridge, hell he never even made it to Uni, yet these plays exist. Go figure.

The experts have summed up the academic argument expertly here. And for reviews of the film, visit here, and here.